In the last post, we looked at kanji that contain 刀 “sword; knife; to cut.” In this post, we are going to look at its variations, a bushu rittoo (刂). The name rittoo comes from 立 “standing” and 刀.

The two shapes 刀 and刂 in kanji had the same shape in ancient writing, and when the last ancient style of writing became kanji that 刂 was used. Just a few months ago we had a chance to look at this change in the kanji 制 and 製 in connection with a bushu kihen. [The Kanji 未妹味昧制製果課裸菓–“tree” (2) on July 19, 2016] In the kanji 制, shown on the right, the left side was a vigorously growing tree with the top thrusting upward, and the left side was a knife. Trimming tree limbs back with a knife or shears means “to regulate.” Now we look at other kanji that have a bushu rittoo.

The two shapes 刀 and刂 in kanji had the same shape in ancient writing, and when the last ancient style of writing became kanji that 刂 was used. Just a few months ago we had a chance to look at this change in the kanji 制 and 製 in connection with a bushu kihen. [The Kanji 未妹味昧制製果課裸菓–“tree” (2) on July 19, 2016] In the kanji 制, shown on the right, the left side was a vigorously growing tree with the top thrusting upward, and the left side was a knife. Trimming tree limbs back with a knife or shears means “to regulate.” Now we look at other kanji that have a bushu rittoo.

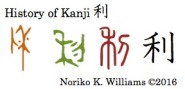

- The kanji 利 “sharp; advantageous”

For the kanji 利, in oracle bone style, in brown, the left side was a knife and the right side was a rice plant with crops. The two dots were probably grains of rice. In bronze ware style, in green, the positions of the knife and the rice plant were switched and the grains are still present. A sharp cutting tool was advantageous in harvesting rice or other crops. In kanji, the knife on the right became two vertical lines and formed a bushu rittoo. The kanji 利meant “sharp” and “useful; advantageous.”

For the kanji 利, in oracle bone style, in brown, the left side was a knife and the right side was a rice plant with crops. The two dots were probably grains of rice. In bronze ware style, in green, the positions of the knife and the rice plant were switched and the grains are still present. A sharp cutting tool was advantageous in harvesting rice or other crops. In kanji, the knife on the right became two vertical lines and formed a bushu rittoo. The kanji 利meant “sharp” and “useful; advantageous.”

There is no kun-yomi. The on-yomi /ri/ is in 鋭利な (“sharp; sharp-edged” /e’eri-na/), 利口な (“clever; bright; shrewd” /rikoo-na/), 便利な (“convenient; useful” /be’nri-na/), and 利用する (“to make good use of” /riyoo-suru/).

- The kanji 別 “to separate”

For the kanji 別, in oracle bone style the right side signified separated bones. Together with a knife on the left, they meant “to separate bones at the joint using a knife.” In ten style, in red, the positions of the two elements got switched. The kanji 別 meant “to separate; another.”

For the kanji 別, in oracle bone style the right side signified separated bones. Together with a knife on the left, they meant “to separate bones at the joint using a knife.” In ten style, in red, the positions of the two elements got switched. The kanji 別 meant “to separate; another.”

The kun-yomi 別れる (“to become separated” /wakare’ru/) and 別れ際 (“on parting” /wakaregiwa/). The on-yomi /betsu/ is in 別々に (“separately” /betsubetsu-ni/), 別居する (“to live separately; live apart” /bekkyo-suru/), 差別 (“discrimination” /sa’betsu/), and 特別に (“particularly; especially” /tokubetsu-ni/).

The next kanji 例 contains 列. The kanji 列 and 烈 have also been discussed previously in connection with the fire. [The Kanji 焦煎烈煮庶遮蒸然燃 –“fire” (2) れっか May 28, 2016]

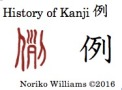

- The kanji 例 “example; custom; that”

For the kanji 例 In ten style the left side was a “person.” The middle and the right side had a beheaded head with the hair still attached and a sword, which signified “to display an enemy’s beheaded heads in a row as a show of victory after a battle,” as previously discussed. For 例, with “person” (イ) added, it signified “people neatly in line.” From that 例 meant “things in a display as a model.” 例 is also used to refer to something previously known to both a speaker and a hearer, “that; usual.”

For the kanji 例 In ten style the left side was a “person.” The middle and the right side had a beheaded head with the hair still attached and a sword, which signified “to display an enemy’s beheaded heads in a row as a show of victory after a battle,” as previously discussed. For 例, with “person” (イ) added, it signified “people neatly in line.” From that 例 meant “things in a display as a model.” 例 is also used to refer to something previously known to both a speaker and a hearer, “that; usual.”

The kun-yomi 例えば /tatoeba/ means “for example.” The on-yomi /re’e/ is in 例 (“example; customs” /re’e/), 例の (“the usual; that one” /re’e-no/, as in 例の話 (“the story that was previously discussed” /re’e-no-hanashi/), 実例 (“actual example” /jitsuree/), 恒例の行事 (“customary event” /kooree-no gyooji/).

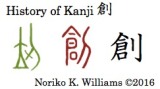

- The kanji 創 “cut; to create”

For the kanji 創, the bronzeware style writing had a standing person on the left and a knife on the right. Together they meant “to be wounded; cut.” In ten style the left side was replaced by a different writing 倉 that had the same sound /so’o/. A knife was used to create something new. So, it also meant “to create.”

For the kanji 創, the bronzeware style writing had a standing person on the left and a knife on the right. Together they meant “to be wounded; cut.” In ten style the left side was replaced by a different writing 倉 that had the same sound /so’o/. A knife was used to create something new. So, it also meant “to create.”

There is no kun-yomi in Joyo kanji. The on-yomi /so’o/ is in 創造する (“to create” /soozoo-suru/). The original meaning of “wound” remains in words such as 絆創膏 (“adhesive bandage” /bansookoo/).

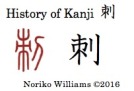

- The kanji 刺 “to sting; pierce; stab”

For the kanji 刺, the left side 朿 was “thorny twigs.” With a “knife” on the right side together, they meant “to sting; pierce; stab.”

For the kanji 刺, the left side 朿 was “thorny twigs.” With a “knife” on the right side together, they meant “to sting; pierce; stab.”

The kun-yomi 刺す /sa’su/ means “to stab; sting,” and is in 虫刺され (“bug bite” /mushisasare/) and 刺身 (“sashimi; slices of raw fish.” The on-yomi /shi/ is in 刺激 (“stimulus; impetus” /shigeki/), 刺繍 (“embroidery” /shishuu/), and 名刺 (“name card” /meeshi/).

- The kanji 前 “front; before”

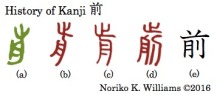

For the kanji 前, In bronze ware style, the top was “a footprint,” and the bottom was a boat. It meant “to move forward.” In the three ten-style writings (b) (c) and (d), the footprint looked more like the kanji 止. (d) had a knife on the bottom right that added the meaning “to cut and even up,” possibly toenails — toenails are in front of your body. The kanji 前 means “front; before.” It is also used to mean “portion.” In kanji, the footprint (止) was simplified to a three-stroke shape.

For the kanji 前, In bronze ware style, the top was “a footprint,” and the bottom was a boat. It meant “to move forward.” In the three ten-style writings (b) (c) and (d), the footprint looked more like the kanji 止. (d) had a knife on the bottom right that added the meaning “to cut and even up,” possibly toenails — toenails are in front of your body. The kanji 前 means “front; before.” It is also used to mean “portion.” In kanji, the footprint (止) was simplified to a three-stroke shape.

The kun-yomi 前 /ma’e/ means “front; before,” and is in 建前 (“façade; the theory” /tatemae/), 後ろ前 (“(to wear clothes) backwards” /ushiro’mae/), 自前 (“one’s own expense” /jimae/), and 持ち前 (“one’s nature; peculiar” /mochimae-no/. The on-yomi /ze’n/ is in 戦前 (“before war”/senzen/) and 前衛 (“avant-garde” /zen-ee/).

The next five kanji 愉癒輸諭喩 share the same component 兪. 兪 is not a Joyo kanji but we have its ancient-style writings shown on the left. Both of the bronzeware style writings had a boat or a tray that was placed vertically. A boat and a tray signified “to transport” something to another place. On the right side was a surgical needle with a big handle at the top and a knife. In ten style, the handle became the top. Together they originally meant “to take lesion out with a knife; heal.”

The next five kanji 愉癒輸諭喩 share the same component 兪. 兪 is not a Joyo kanji but we have its ancient-style writings shown on the left. Both of the bronzeware style writings had a boat or a tray that was placed vertically. A boat and a tray signified “to transport” something to another place. On the right side was a surgical needle with a big handle at the top and a knife. In ten style, the handle became the top. Together they originally meant “to take lesion out with a knife; heal.”

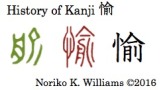

- The kanji 愉 “pleasure”

For the kanji 愉, the bronzeware style writing was the same as that of 兪 “to take lesion out with a knife; recover.” In ten style a heart (忄) was added on the left. Removing the source of concern from the heart meant “pleasure; joy.” In kanji, the knife became a bushu rittoo shape.

For the kanji 愉, the bronzeware style writing was the same as that of 兪 “to take lesion out with a knife; recover.” In ten style a heart (忄) was added on the left. Removing the source of concern from the heart meant “pleasure; joy.” In kanji, the knife became a bushu rittoo shape.

There is no kun-yomi. The on-yomi /yu/ is in 愉快 (“pleasant; delightful; cheerful” /yu’kai/).

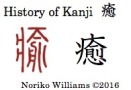

- The kanji 癒 “healing; cure”

The ten-style writing of the kanji 癒 had a bed (爿), vertically placed for space, on the left, and a horizontal line at the top of 兪, which signified a sick person. Together they mean a sick person getting healed from an illness by having a lesion removed with a surgical knife. In kanji the bed and the sick person became a bushu yamaidare (疒) “sick; illness,” and a “heart” (心) was added to indicate “feeling better; healing from an illness.” The kanji 癒 meant “cure: heal.”

The ten-style writing of the kanji 癒 had a bed (爿), vertically placed for space, on the left, and a horizontal line at the top of 兪, which signified a sick person. Together they mean a sick person getting healed from an illness by having a lesion removed with a surgical knife. In kanji the bed and the sick person became a bushu yamaidare (疒) “sick; illness,” and a “heart” (心) was added to indicate “feeling better; healing from an illness.” The kanji 癒 meant “cure: heal.”

The kun-yomi 癒す /iya’su/ means “to cure; heal,” and its passive form 癒される /iyasare’ru/ means “therapeutic; healing.” The on-yomi /yu/ is in 治癒 (“healing; recovery” /chi’yu/).

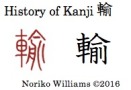

- The kanji 輸 “to transport”

For the kanji 輸, in ten style the left side was a “vehicle” (車). The right side “taking out a lesion” gave the meaning “to take something out to another place.” Together they meant “to move something; transport.”

For the kanji 輸, in ten style the left side was a “vehicle” (車). The right side “taking out a lesion” gave the meaning “to take something out to another place.” Together they meant “to move something; transport.”

There is no kun-yomi. The on-yomi /yu/ is in 輸出 (“export” /yushutsu), 輸入 (“import” /yunyuu/), 輸送 (“transportation; carriage” /yusoo/) and 運輸 (“transportation; conveyance” /u’n-yu/.)

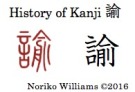

- The kanji 諭 “to admonish for an error; discourage”

The ten-style writing of the kanji 諭 had a bushu gonben “word; to say.” Together with 兪, they meant “to admonish someone for an error; advise,” as if one took the lesion out. The kanji 諭 means “to admonish someone for an error; counsel; discourage.”

The ten-style writing of the kanji 諭 had a bushu gonben “word; to say.” Together with 兪, they meant “to admonish someone for an error; advise,” as if one took the lesion out. The kanji 諭 means “to admonish someone for an error; counsel; discourage.”

The kun-yomi /sato’su/ means “to admonish someone for an error; advise.” The on-yomi /yu/ is in 教諭 (“teacher at elementary and high schools” /kyooyu/).

- The kanji 喩 “example; metaphor”

There is no ancient writing available for 喩. The left side 口 “to speak” and the right side 兪together meant “to teach something with a metaphor.”

The kun-yomi 喩え /tato’e; tato’i/ is not a Joyo kanji reading but means “example; metaphor.” The on-yomi /yu/ is in 比喩 (“metaphor” /hi’yu/).

In the next post, we will look at a few more kanji 刃忍認 that are related to a knife, and then start a topic on other sharp-edged objects. [November 6, 2016] -Noriko