In this post we are going to look at a person with his mouth wide open, 欠, which is called bush akubi or kentsukuri.

(1) 欠 “to lack; want of”

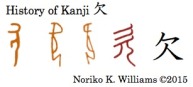

The current use of the kanji 欠 had two different shapes, 欠 and 缺, in its development. On the left, we have three samples of oracle bone style for 欠, in brown, – a standing person facing left, a kneeling person facing left, and another kneeling person facing right. All of them were viewed from the side and had a mouth that was open wide and tilted slightly upward. It signified a person “exhaling or inhaling air,” and a posture that was related to singing (as in 歌) or drinking or swallowing (as in 飲). In ten style, in red, the head became three hooked lines and the bottom had arms and a torso and legs that were kneeling, which in kanji became the shape 人. How did the meaning “exhaling or inhaling air” come to be the current meaning of “lack of; want of”? The answer lies in the kyuji 缺, which was not related to 欠 in meaning or shape. The development of 缺 is shown on the right.

The current use of the kanji 欠 had two different shapes, 欠 and 缺, in its development. On the left, we have three samples of oracle bone style for 欠, in brown, – a standing person facing left, a kneeling person facing left, and another kneeling person facing right. All of them were viewed from the side and had a mouth that was open wide and tilted slightly upward. It signified a person “exhaling or inhaling air,” and a posture that was related to singing (as in 歌) or drinking or swallowing (as in 飲). In ten style, in red, the head became three hooked lines and the bottom had arms and a torso and legs that were kneeling, which in kanji became the shape 人. How did the meaning “exhaling or inhaling air” come to be the current meaning of “lack of; want of”? The answer lies in the kyuji 缺, which was not related to 欠 in meaning or shape. The development of 缺 is shown on the right.

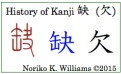

The kyuji 缺 for 欠: In the ten style of 缺, the left side was clayware or earthenware, which was easily chipped. The right side had a weapon at the top and a hand at the bottom and it signified “to break.” Together chipped or broken earthenware or just stuff, in general, meant “not complete” or “not sufficient.” The kyuji, in blue, reflected the ten-style shape. In shinjitai, however, the kanji 缺 was replaced by the phonetically same 欠, even though the two kanji 缺 and 欠 did not share the same origin. The meaning that the shape 欠 originally had, which was kept in the component of other kanji (“opening one’s mouth open to take in air, food or drink”), overlapped the meaning of “want of; to lack” that the kanji 缺 had. In shinjitai, the simpler shape must have won over, making 缺 a shape of the past.

The kyuji 缺 for 欠: In the ten style of 缺, the left side was clayware or earthenware, which was easily chipped. The right side had a weapon at the top and a hand at the bottom and it signified “to break.” Together chipped or broken earthenware or just stuff, in general, meant “not complete” or “not sufficient.” The kyuji, in blue, reflected the ten-style shape. In shinjitai, however, the kanji 缺 was replaced by the phonetically same 欠, even though the two kanji 缺 and 欠 did not share the same origin. The meaning that the shape 欠 originally had, which was kept in the component of other kanji (“opening one’s mouth open to take in air, food or drink”), overlapped the meaning of “want of; to lack” that the kanji 缺 had. In shinjitai, the simpler shape must have won over, making 缺 a shape of the past.

The kun-yomi 欠く /kaku/ means “to lack; to chip; nick.” It is in phrases such as 欠くことができない (“indispensable” /kakukoto’-ga deki’nai/), 欠けている (“is chipped; lacking” /kaketeiru/). The on-yomi /ke’tsu/ is in 欠席 (“absence” /kesseki/), 欠点 (“fault; shortcoming; defect” /kette’n/), and 不可欠な (“indispensable; essential” /huka’ketsu-na/). The original meaning of 欠 is also used in 欠伸 (“yawning” /akubi/). (Please note that 欠く /kaku/ is an unaccented word whereas 書く /ka’ku/ “to write” is an accented word.)

(2) 吹 “to blow”

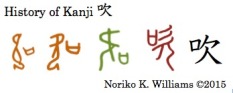

This kanji has the shape 口 added to the shape 欠. In the two samples of oracle bone style, the kneeling person was placed on the left, each facing an opposite direction, and had 口 on the right side. In bronze ware style, in green, and ten style, a person and 口 were placed in front of a person. It meant a person opening his mouth big and blowing air. That has been the traditional explanation. Shirakawa treated 口 as a prayer box throughout his books. Was the shape 口 just an emphasis of a mouth or a prayer box? Let us leave that question unsolved here. The kanji 吹 means “to blow; puff.”

This kanji has the shape 口 added to the shape 欠. In the two samples of oracle bone style, the kneeling person was placed on the left, each facing an opposite direction, and had 口 on the right side. In bronze ware style, in green, and ten style, a person and 口 were placed in front of a person. It meant a person opening his mouth big and blowing air. That has been the traditional explanation. Shirakawa treated 口 as a prayer box throughout his books. Was the shape 口 just an emphasis of a mouth or a prayer box? Let us leave that question unsolved here. The kanji 吹 means “to blow; puff.”

The kun-yomi 吹く /hu’ku/ is used in 風が吹く(“the wind blows” /kaze-ga hu’ku/), 口笛を吹く (“to blow a whistle” /kuchibu’e-o hu’ku/) and 吹き出す (“to spout; puff; to burst into laughter” /hukida’su/). It is also used for the word 吹雪 (“snow storm; blizzard” /hu’buki/). The on-yomi /su’i/ is in 吹奏楽 (“wind instrument music” /suiso’ogaku/).

(3) 次 “next; following”

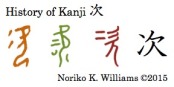

For the kanji 次, there are a couple of different interpretations. One view is that it is a person breathing out (two lines on the left signified breath) and lamenting, which signified asking the god’s will (which are in the kanji such as 諮 “to consult”). ニ was phonetically used to mean “secondary; again” and “following; next.” It meant “to lament; following; next.” Another view is that ニ was phonetically the same as 止 “to stop” and 欠 signified resting and yawning. Together they meant a traveler resting for the next move. It meant “next.” So either view seems to work all right.

For the kanji 次, there are a couple of different interpretations. One view is that it is a person breathing out (two lines on the left signified breath) and lamenting, which signified asking the god’s will (which are in the kanji such as 諮 “to consult”). ニ was phonetically used to mean “secondary; again” and “following; next.” It meant “to lament; following; next.” Another view is that ニ was phonetically the same as 止 “to stop” and 欠 signified resting and yawning. Together they meant a traveler resting for the next move. It meant “next.” So either view seems to work all right.

The kun-yomi 次 /tsugi’/ means “next; following,” and is in 次に (“next; after this” /tsugi’-ni/), 相次いで (“one after another” /a’itsuide/), and 次々に (“one after another” /tsugi’tsugi-ni/). The on-yomi /ji/ is in 次回 (“next time” /ji’kai/) and 目次 (“table of contents” /mokuji/).

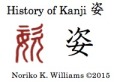

(4) 姿 “appearance; figure”

The kanji 姿 consists of two shapes 次 and 女. In ten style the top left had two lines ニ, and the bottom was 女 “woman.” The right side was 欠. Together a woman preparing herself in good order meant “figure; form; appearance.”

The kanji 姿 consists of two shapes 次 and 女. In ten style the top left had two lines ニ, and the bottom was 女 “woman.” The right side was 欠. Together a woman preparing herself in good order meant “figure; form; appearance.”

The kun-yomi /su’gata/ means “appearance; figure; form” and is in 晴れ姿 (“appearance in one’s shining moment” /haresu’gata/) and 後ろ姿 (“appearance from behind” /ushirosu’gata/). The on-yomi /shi/ is in 姿勢 (“attitude; posture” /shisee/) and 容姿 (“appearance” /yo’oshi/).

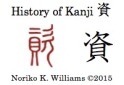

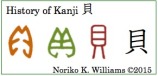

(5) 資 “resources; capital”

Another kanji that contains 次 is 資. In ten style the bottom left was a cowry. A cowry came from the southern sea in a faraway place. It appeared in a number of kanji signifying something valuable.

Another kanji that contains 次 is 資. In ten style the bottom left was a cowry. A cowry came from the southern sea in a faraway place. It appeared in a number of kanji signifying something valuable.  The development of the kanji 貝 “shell,” starting from an image of a cowry, is shown on the right. A cowry was not a bivalve (二枚貝 /nima’igai/) but a snail (巻貝 /maki’gai/). The image captured in oracle bone style had an opening. (Because this shape is so important to other kanji, it deserves its own posting later on.) The shape 次 was used phonetically here. The kanji 資 meant “resources; capital.”

The development of the kanji 貝 “shell,” starting from an image of a cowry, is shown on the right. A cowry was not a bivalve (二枚貝 /nima’igai/) but a snail (巻貝 /maki’gai/). The image captured in oracle bone style had an opening. (Because this shape is so important to other kanji, it deserves its own posting later on.) The shape 次 was used phonetically here. The kanji 資 meant “resources; capital.”

There is no kun-yomi in the Joyo-kanji. The on-yomi /shi/ is in 資本 (“capital”/shihon/), 資格 (“qualification; license” /shikaku/), and 資料 (“data; material” /shi’ryoo/).

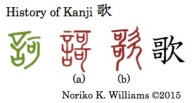

(6) 歌 “to sing; song”

In the bronzeware style of the kanji 歌 the left side was the old form of 言 “word; language.” The right side was 可.

In the bronzeware style of the kanji 歌 the left side was the old form of 言 “word; language.” The right side was 可.  We have a fuller picture of the history of 可, shown on the right side.

We have a fuller picture of the history of 可, shown on the right side.

The kanji 可: The oracle bone style of 可 had a bent shape and 口. For simplicity, we take 口 here as a mouth. A bent shape signified that voice did not come out straight and was forced. Singing a song was one voicing words with some effort.

Back to the left side of 歌. As the ten style writing of 歌, Setsumon showed two shapes (a) and (b). The writing (a) had “words” on the left and 哥, two 可, on the right. In (b), 哥 “forced voice” was placed on the left and the right side became 欠 – “someone opening his mouth wide open.” Together they meant “to sing.” I wonder which composite shape of (a) and (b) would represent better to mean “to sing; song.” You decide.

The kun-yomi 歌う /utau/ means “to sing” and 歌 /uta’/ is “song.” The on-yomi /ka/ is in 歌手 (“singer” /ka’shu/), 国歌 (“national anthem” /ko’kka/), 演歌 (“enka song” /e’nka/), 歌謡曲 (“popular song” /kayo’okyoku/), and 歌曲 (“song,” usually a classical song. /ka’kyoku/).

(7) 飲 “to drink; swallow”

The last kanji we look at in this post is 飲. The kanji 飲 had humorous images of writing in the beginning. In oracle bone style, the left side had a sake or rice wine cask that had a stopper at the top, and the right side was a person drinking rice wine out of it. From the way he was leaning over the cask, he must have been enjoying drinking very much! I always like oracle bone style writing because you can have a glimpse of a real person in ancient times. In bronze ware style, the left sample only had the wine cask whereas the right side had a person with his tongue out signifying that he was not just standing next to it but drinking. The left side of the ten-style writing consisted of a lid (今) at the top and a rice wine cask 酉 below, and the right side was a person 欠. Together they made a good story. However, in kyuji, the left side was replaced by a totally different shape, the old form of a bushu shokuhen.

The last kanji we look at in this post is 飲. The kanji 飲 had humorous images of writing in the beginning. In oracle bone style, the left side had a sake or rice wine cask that had a stopper at the top, and the right side was a person drinking rice wine out of it. From the way he was leaning over the cask, he must have been enjoying drinking very much! I always like oracle bone style writing because you can have a glimpse of a real person in ancient times. In bronze ware style, the left sample only had the wine cask whereas the right side had a person with his tongue out signifying that he was not just standing next to it but drinking. The left side of the ten-style writing consisted of a lid (今) at the top and a rice wine cask 酉 below, and the right side was a person 欠. Together they made a good story. However, in kyuji, the left side was replaced by a totally different shape, the old form of a bushu shokuhen.

The kanji 食: To see that the bushu shokuhen came from an origin that was totally different from 飲, I am showing the development of the kanji 食 “food; to eat” on the right side. In oracle bone style and bronze ware style, it was food heaped on a dish with a lid on top. In ten style the bottom took the shape that was the same as the person that we looked at in the last two posts. We saw that in ten style that shape had the meaning of “person; spoon; ladle.”

The kanji 食: To see that the bushu shokuhen came from an origin that was totally different from 飲, I am showing the development of the kanji 食 “food; to eat” on the right side. In oracle bone style and bronze ware style, it was food heaped on a dish with a lid on top. In ten style the bottom took the shape that was the same as the person that we looked at in the last two posts. We saw that in ten style that shape had the meaning of “person; spoon; ladle.”

Now back to the kyuji 飮, in which the bottom has two lines. I imagine that this was the remnant of the ten style writing of 食 at the bottom. In shinjitai, the bushu shokuhen has a short stroke at the end.

The kun-yomi 飲む “to drink, to swallow” is also used in 薬を飲む (“to take medicine” /kusuri o no’mu/), 飲み物 (“drink, beverage” /nomi’mono/) 飲み食い (“eating and drinking” /no’mikui/). On-yomi /i’n/ is in 飲食店 (“restaurant; eatery” /insho’kuten/), 飲酒運転 (“drunken driving” or “driving under the influence of alcohol”), and 飲用水 (“drinking water” /in-yo’osui/).

Our exploration of kanji that originated from the posture of one’s whole body continues in the next post. [April 11, 2015]