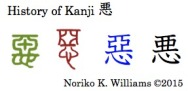

(1) The kanji 悪 “bad; vice” and 亞 “secondary; Asia”

For the kanji 悪, the top of the bronze ware style, in green, and ten style, in red, was a foundation or base of a mausoleum, with columns at the four corners. By itself, it is the kanji 亜.

For the kanji 悪, the top of the bronze ware style, in green, and ten style, in red, was a foundation or base of a mausoleum, with columns at the four corners. By itself, it is the kanji 亜.

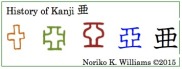

The kanji 亞 — The history of the kanji 亜 is shown on the right side. (Oracle bone style, in brown) From a foundation of a structure, it signified something being suppressed. In kyuji, in blue, the four corners showed better than the shinjitai (亜). Having the meaning of something underground, the kanji 亜 meant “secondary; not authentic.” It was also used phonetically for /a/ in the words such as 亜細亜 (“Asia” /a’jia/) and 亜流 (“secondary; imitator; follower” /aryuu/). I always find the use of the kanji 亜 for “Asia” puzzling. I have not had a chance to look into it.

The kanji 亞 — The history of the kanji 亜 is shown on the right side. (Oracle bone style, in brown) From a foundation of a structure, it signified something being suppressed. In kyuji, in blue, the four corners showed better than the shinjitai (亜). Having the meaning of something underground, the kanji 亜 meant “secondary; not authentic.” It was also used phonetically for /a/ in the words such as 亜細亜 (“Asia” /a’jia/) and 亜流 (“secondary; imitator; follower” /aryuu/). I always find the use of the kanji 亜 for “Asia” puzzling. I have not had a chance to look into it.

For the kanji 悪 the bottom had 心 “heart.” Together they signified “bad feelings that were suppressed” and it is used to mean “bad; vice; evil.” The kun-yomi /wa’ru/ is in 悪い (“bad” /waru’i/) and 意地悪な (“wicked; spiteful” /iji’waruna/). Another kun-yomi /a/ is in 悪しき(“bad” /a’shiki/). The on-yomi /a’ku/ is in 悪 (“evil; badness; vice” /a’ku/), 悪人 (“villain” /akunin/), and 悪事 (“evil deed” /a’kuji/). Another on-yomi /o/ is in 嫌悪感 (“feeling of abhorrence” /ken-o’kan/) and 悪寒がする (“to shiver; shake (with a fever)” /okan-ga-suru/).

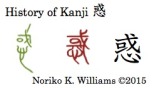

(2) The kanji 惑 “to be confused; bewildered” and 或 “or”

In the bronzeware style of the kanji 惑, the top 或 was “an area that was protected with a halberd”, and the bottom was “a heart.” The top 或 by itself had the meaning “to have a doubt,” and is in the word 或は (“perhaps; maybe; or” /aru’iwa/). Together they meant a state of mind that was not certain. The kanji 惑 means “to be confused; bewildered.”

In the bronzeware style of the kanji 惑, the top 或 was “an area that was protected with a halberd”, and the bottom was “a heart.” The top 或 by itself had the meaning “to have a doubt,” and is in the word 或は (“perhaps; maybe; or” /aru’iwa/). Together they meant a state of mind that was not certain. The kanji 惑 means “to be confused; bewildered.”

The kanji 或 “perhaps; or”: The kyuji 國 (for 国) “country” and 惑 came from the same origin — “an area protected by a halberd” or “to exist.” The kanji 或 is not included on the Joyo kanji list, even though the word /aru’iwa/ is an everyday word in speaking.

The kun-yomi /mado’u/ 惑う means “to be confused; go astray,” and is in 惑わされる (“to be misled by” /madowasare’ru/) and 戸惑う (“to be puzzled; feel at a loss” /tomado’o/). The on-yomi /wa’ku/ is in 迷惑な (“annoying; inconvenient; troublesome” /me’ewaku-na/) and in 惑星 (“primary planet” /wakusee/)– because it circles around the earth! The expression 不惑 /hu’waku/ means “to be at the age of forty,” from the belief that this is when one is supposed to be free from vacillation. Hmmm….

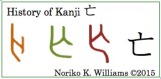

(3) The kanji 忘 “to forget” and 忙 “busy”

The top of the kanji 忘 by itself is the kanji 亡 “not to exist; to disappear.”

The top of the kanji 忘 by itself is the kanji 亡 “not to exist; to disappear.”  The history of the kanji 亡 is shown on the right.

The history of the kanji 亡 is shown on the right.

A couple of different views on the origins here. One is that it was a person and a screen and that one disappeared when he died, thus “to disappear.” Another view is that it was deceased with his bones bent and signified “to disappear.” The kanji 亡 meant “to pass away; to die.”

Now back to the kanji 忘. With a “heart” added at the bottom, it meant that something disappeared from the mind, that is, “to forget.” The kun-yomi 忘れる /wasureru/ means “to forget,” and is in 忘れ物 (“leaving something behind inadvertently; lost article” /wasuremono/.) The on-yomi /bo’o/ is in 忘年会 (“end-of-the-year party” /boone’nkai/), a party letting the year pass by.

A related kanji we should not leave out here is the kanji 忙 “busy.” There is no ancient writing available because it did not exist in ancient times. The components of the kanji are a heart (in this case, the bushu risshinben) and the kanji 亡 “to disappear.” Together they originally meant “to be dazed; with a blank look.” When one is very busy he becomes absent-minded. The kanji 忙 means “busy.” Clever use of the two existing components.

The kun-yomi 忙しい means “busy.” The phrase ご多忙中のところ /gotaboochuu-no-tokoro/ “during the time when you are very busy” is used in a polite expression for thanking someone for “taking so much of your valuable time.”

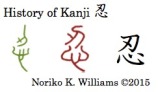

(4) The kanji 忍 “endurance”

The top of the kanji 忍 in ten style was a knife with a dot, which pointed out the blade. By itself, 刃 /ha/ means “blade.” Its on-yomi /ji’n/ also had the meaning “something strong and resistant.” With a heart at the bottom, the kanji 忍 meant “to endure; brave out.”

The top of the kanji 忍 in ten style was a knife with a dot, which pointed out the blade. By itself, 刃 /ha/ means “blade.” Its on-yomi /ji’n/ also had the meaning “something strong and resistant.” With a heart at the bottom, the kanji 忍 meant “to endure; brave out.”

The kun-yomi 忍ぶ /shino’bu/ means “to endure; brave out.” The on-yomi /ni’n/ is in 忍耐 (“endurance” /ni’ntai/) and 忍者 (“ninja spy” /ni’nja/). Out of curiosity, I have just looked up the Oxford American Dictionary for ninja. The definition was “a person skilled in ninjutu.” Then what is /ni’njutsu/ (忍術)? It says, “The traditional Japanese art of stealth, camouflage, and sabotage, developed in feudal times for espionage and now practiced as a martial art” (New Oxford American Dictionary). That covers it all!

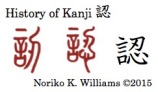

(5) The kanji 認 “to accept; recognize”

The two ten-style writings for the kanji 認 had “word; language” on the left. The right side had either a blade of a knife, or a heart with a knife, and was used phonetically for /ji’n/ to mean “to ensure.” Together they meant to listen patiently to what another person had to say and accept it. The kanji 認 meant “to accept” or “to recognize.”

The two ten-style writings for the kanji 認 had “word; language” on the left. The right side had either a blade of a knife, or a heart with a knife, and was used phonetically for /ji’n/ to mean “to ensure.” Together they meant to listen patiently to what another person had to say and accept it. The kanji 認 meant “to accept” or “to recognize.”

The kun-yomi 認める /mitomeru/ means “to accept; acknowledge; recognize,” and is in 認め印 (“stamp for receipt” /mitomein/). When you receive a package, the delivery person asks you, saying,「認め印お願いします」(“Please press your name stamp here.” /mitomein onegai-shima’su/), instead of your signature. A Japanese person buys an inexpensive stamp of the family name in kanji for this kind of informal purpose, which would not be used for a bank account or other important documents. The on-yomi /ni’n/ is in 確認する (“to confirm” /kakunin-suru/), 認定 (“certification” /nintee/), 否認する (‘’to deny” /hinin-suru/) and 認可する (“to grant permission” /ni’nka-suru/).

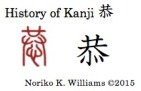

(6) The kanji 恭 “respectfully; reverentially”

We have been looking at the kanji that have two bushu, the bushu kokoro 心, which comes at the bottom, and the bushu risshinben, which comes on the left side. There is one more bushu shape that came from a heart. The inside of the bottom of the kanji 恭 is called /shitago’koro/ and has four strokes, the second of which is longer, perhaps for the artery in the ancient shape of a heart.

In the ten style of 恭, the top had the making of the kanji 共, in which two hands were raising something to show the humbleness of the bearer. Inside the two hands was a heart. Together they meant “respectfully; reverentially.” It is not a productive kanji other than the kun-yomi word 恭しく (“respectfully; reverentially” /uyauyashi’ku/) and the on-yomi word 恭順 (“dutiful submission (to an order)” /kyoojun/). The word 恭順 /kyoojun/ is not an everyday life word at all. The occasion that comes to my mind is the term that historians used to describe the act of transferring power when the last Tokugawa Shogun was submitted to the Emperor in 1868. [We have looked at the kanji 共 in the May 31, 2014 posting.]

In the ten style of 恭, the top had the making of the kanji 共, in which two hands were raising something to show the humbleness of the bearer. Inside the two hands was a heart. Together they meant “respectfully; reverentially.” It is not a productive kanji other than the kun-yomi word 恭しく (“respectfully; reverentially” /uyauyashi’ku/) and the on-yomi word 恭順 (“dutiful submission (to an order)” /kyoojun/). The word 恭順 /kyoojun/ is not an everyday life word at all. The occasion that comes to my mind is the term that historians used to describe the act of transferring power when the last Tokugawa Shogun was submitted to the Emperor in 1868. [We have looked at the kanji 共 in the May 31, 2014 posting.]

Well, I think we stop our exploration of the kanji that have a heart here. There were quite a lot already. We need to move on to other kanji. We have learned in the last five postings, in terms of shape in kanji, it comes in three different shapes, kokoro, risshinben and shitagokoro. In terms of meaning, these kanji deal with the physical features of a heart, emotions, and the state or activity of one’s mind.

In the next several posts, we continue to look at the component that originally comes from a physical feature. [March 7, 2015.]